A Study of Landscapes Featuring Tainan Scenery from the 1st to the 5th Taiten

Text / CHOU Hsin

I. Origin

Taiwanese art gradually matured during the period of Japanese rule. After the Meiji Restoration, Japan introduced ideas of natural sciences, humanities, and social sciences into Taiwan, launching the island’s modernization through infrastructural construction and education. In 1927, the Office of the Governor-General of Taiwan annually organized the Taiten (“Taiwan Fine Arts Exhibition”) and advocated portraying Taiwanese characteristics through the idea of “local color.” This was how the Office of the Governor-General of Taiwan defined and interpreted the idea of the “local.” The judges at the Taiten emphasized observations made by “painting from life,” which denoted modern implications—these included the application of the perspective and the vibrant colors used to depict the scenery of this southern island. As a result, elements of pleinairism and local features constituted the mainstream style of government-sponsored art exhibitions. Furthermore, among the artworks selected for these exhibitions, the largest group comprised landscape paintings.

Maruyama Banka divided Taiwanese landscape painting into two types: those depicting historical sceneries and those delineating lyrical scenes. The former features well-known historical sites and landmarks, allowing the spectator to reminisce about ancient history and perceive the sceneries of places. The latter, on the other hand, engages the spectator’s sensibility and feelings with theatrical expression, unfurling lyrical expressions on canvases. Tainan, as a historical city, has a plethora of iconic monuments informed by historical meanings, making the city a frequent destination for both Japanese and Taiwanese artists in their painting trips. From 1933 to 1935, Liao Chi-Chun and Umehara Ryuzaburo had traveled together to paint the Confucius Temple three times. Ishikawa Kinichiro and Kawashima Riichiro also mentioned the beauty of Tainan’s historical monuments in their travelogues. Among the landscapes featuring Tainan’s sceneries that were selected for the Taiten, nearly half of them depicted the subject of historical monuments, and the other half mainly featured modernized facilities. So, this study will be divided into two parts for further exploration: (I) The Past and Present of an Ancient City and Its Historical Sites: the Confucius Temple, City Gates, the Theological College and Seminary, and Other Temples, and (II) Sensibility-based Experiences in Modern Life: Roundabouts, Parks, Streets, and Canals.”

This study continues “A Study of Landscapes of Tainan in the Catalogues of the Taiten and the Futen during the Period of Japanese Rule,” a research project of the Taiwan Visual Art Archive (TVAA) that studied sixty-eight landscapes featuring recognizable Tainan sceneries selected for the Taiten and the Futen (Taiwan Viceroy Art Exhibition). This essay focuses on these Tainan-themed landscapes selected from the 1st to the 5th Taiten, and selects thirty-five pieces that have specific titles and depict recognizable landmarks in Tainan. After the Ming and Qing dynasties and the period of Japanese rule, how did the historicity and the sense of place of the same sceneries change? How did the artists represent their sensory experiences amidst the changes of the old and the new eras? Through this approach, this essay aims to re-explore the local context of the Tainan’s sceneries to deepen the general understanding of local art history and connect the sensibility of the past and the present times.

II. Scope and Method

The research scope of the “Tainan-themed” landscapes encompasses the area of the Tainan Prefecture during the period of Japanese rule, namely, modern-day Tainan City, Chiayi City and County, and the areas of Huwei, Douliu, and Beigang in Yunlin. Based on this scope, the landscapes of Tainan selected from the 1st to the 5th Taiten can be roughly divided into “the early period of Japanese rule” and the “latter period of Japanese rule.” The former includes ancient temples, historical monuments, and Western-style buildings, and the latter mainly looks at modern facilities, such as roundabouts, markets, streets, and parks, exploring these topics through the division of “The Past and Present of an Ancient City and Its Historical Sites: the Confucius Temple, City Gates, the Theological College and Seminary, and Other Temples” and “Sensibility-based Experiences in Modern Life: Roundabouts, Parks, Streets, and Canals.”

Works in the part of “the early period of Japanese rule” include twelve pieces, namely, Lin Yu-Shan’s Great South Gate; Jyo Seiren’s Wenling Matsu Temple in Chiayi; Liao Chi-Chun’s Dusk at Yingchun Gate; Misono Nobuya’s Dongyue Temple in Tainan; East Gate in Summer by Sai Botatsu (Tsai Ma-Ta); Liao Pao-Sung’s Yuedi Temple; Shi Yu-Shan’s Festival of Chaotian Temple; Kuo Po-Chuan’s Alley in Front of Kuan Ti Temple; Red Gate by Chyo Gayu (Chao Ya-You); The Temple in the Afternoon by Kyo Kin-Rin (Hsu Chin-Lin); Hara Susumu’s Tainan Theological College and Seminary; and Takei Shyoichi’s In the Forest. Those discussed in “the latter period of Japanese rule” include Kuwano Ryokiti’s The Canal with a Marabutan and Wharf; Chen Ken-Chin’s Chikan Street in Tainan; Takahashi Kiyoshi’s A Backstreet in Tainan, Tainan in September, and Lebbek; Liao Chi-Chun’s Street, Early Summer, and Market; Tsai Ma-Da’s The Autumn of Hutoupi; A Morning of the Tainan Canal by Ko Kin-Kan (Kao Chun-Chien); Wu Nai-Ting’s The Morning of Hutoupi; Nashima Mitsugi’s The Junks; Misono Nobuya’s Sunset on the Canal; and Oshimoto Teruo’s A Backstreet in Tainan, which are fifteen works in total. The three paintings depicting Tainan Prefecture’s natural sceneries but with unidentifiable locations are Nashima Mitsugi’s Scenery of Anping; Sunset by Lin Tourei (Lin Dong-Ling); and Lin Yu-Shan’s Lotus Pond.

This essay will first concentrate on the Tainan-themed landscapes that were selected for the 1st to the 5th Taiten during the period of Japanese rule. Based on the criteria mentioned above, these works are divided into two parts: the early and latter periods of the Japanese rule, before they are grouped by location. Through examining online and personally visiting these locations to confirm the actual spots, they are pinpointed on historical and modern maps for an area and location analysis. The essay will then discuss the connection between Tainan’s history and localness while exploring the line of sight in these Tainan-themed landscapes by inspecting the artistic expression and approaches.

III. Tainan Sceneries in the Landscapes from the 1st to the 5th Taiten

(I) The Past and Present of an Ancient City and Its Historical Sites: the Confucius Temple, City Gates, the Theological College and Seminary, and Other Temples

During the period of Dutch Rule, the Dutch conducted business and built a city in Anping, historically known as “Tayouan,” which was the earliest international city in Taiwan. During this period, Fort Zeelandia (now Anping Old Fort) and Fort Provintia (now Chikan Tower) began to take shape as fortresses and local political centers. Today, they are still important historical monuments and symbols of the city. Throughout the Ming and Qing dynasties, Han Chinese culture and Western culture continued to enter Tainan, adding historical elements and an exotic feel to the city. The Confucius Temple, city gates, temples, Western-style houses, and the seminary were all subjects favored by artists. Compared to modern facilities, such as new-style streets and houses, visiting ancient monuments and sites became a historical and mysterious topic for Taiwanese and Japanese artists alike. Meanwhile, they also brought a sense of the past into the modern-style constructions. This section will study and analyze twelve works delineating the historical monuments and sceneries showcased from the 1st to the 5th Taiten during the early period of Japanese rule.

1. City Gates

Since the rule of the Qing dynasty (circa 1725), Tainan began building the city’s wooden fences and its fourteen gates. In 1895, due to the Japanese siege on three sides of the city, many parts of its walls were destroyed and consequently torn down. Only a small percentage of the city walls were preserved and renovated due to the urban planning project of 1901 to serve as one of the characteristic features of beautification and modernization. Artists including Lin Yu-Shan, Liao Chi-Chun, and Sai Botatsu (Tsai Ma-Ta) painted the south gate (fig. 2) and the east gate (fig. 4).

The uniqueness of the city gates was discussed in Ishikawa Kinichiro’s essay “Kogarashi no niwa” (Gardens in Winter Wind), in which the artist mentioned the incredibly elegant appearance of Tainan’s gates. To Ishikawa, these gates possessed the value of national treasures and were comparable to the gates of ancient Rome. So, around the 1st Taiten, he published a series of watercolors that were collectively titled “Taiwan’s Rome” in Taiwan Nichi Nichi Shin Po. A majority of these watercolors featured the Tainan’s city gates as the theme, which showed the artist’s love for the city gates of Tainan.

【Fig. 1】 Lin Yu-Shan, Great South Gate, 1927, the 1st Taiten

【Fig. 2】 An old photo of the south gate in 1905.

Source: Digital Collections of the National Taiwan University Library

In 1927, Lin Yu-Shan’s Great South Gate (fig. 1) was selected for the 1st Taiten. When commenting on Water Buffalo, another piece by Lin that was selected for the Taiten in the same year, Tousui Nishioka stated that “it was hard to believe that [Water Buffalo] was painted by the same artist who also painted Great South Gate on view in the third gallery room.” He went on to point out the compositional flaws of the latter, saying that the gate tower looked unnatural and flat, which indicated that the artist was not yet able to master the technique of perspective. However, the overall desolate mood of the piece perfectly demonstrated the dilapidated situation of the gate tower before it was renovated by the government in 1927. As shown in the old photograph, the city gate and walls were ruinous. Though the angle of Lin’s painting differed from that of the photo, the rolling walls in the background were somehow visible. Immersed in wild grass, the bleak landscape shares a quality similar to that of Ishikawa’s “Taiwan’s Rome” series, which exuded a desolate, nostalgic atmosphere. Lin might have heard of the upcoming renovation of the south gate that year, which brought him to paint the landscape and record this memory forever.

【Fig. 3】 Liao Chi-Chun, Dusk at Yingchun Gate, 1928, the 2nd Taiten

Source: Catalogue of the 2nd Taiten

【Fig. 4】 An old photo of the east gate in 1920.

Source: Digital Collections of the National Taiwan University Library

【Fig. 5】 Sai Botatsu (Tsai Ma-Ta), East Gate in Summer, 1928, the 2nd Taiten

Source: Catalogue of the 2nd Taiten

In comparison, the east gate painted by Liao Chi-Chun and Sai Botatsu (Tsai Ma-Ta) convey a livelier atmosphere. In 1901, the government announced a city planning project, and the east gate was redesigned as a roundabout and green park, which allowed the historical monument to be preserved. As a matter of fact, Tainan has the highest density of roundabouts in Taiwan. This was because of Nagano Junzo, the chief technician of the city planning committee at that time. After Nagano visited the World Expo in Paris in 1900. He brought back the radial street plan of Paris, with the Arc de Triomphe as the center, and applied the design to Tainan, creating the unusual juxtaposition of a grid street plan and a radial street plan in the cityscape while contributing to the formation of an invisible network comprising separated quarters of Japanese residents and Taiwanese people in the city.

A vintage photo from 1920 shows a straight road leading to the east gate with houses lining both sides and a utility pole in sight, which is a symbol of modernization. Liao Chi-Chun’s Dusk at Yingchun Gate (fig. 3) was painted with unfettered brushwork that highlighted the flow of crowds. Since the Qing dynasty’s rule, this area had a cluster of sugar refineries and warehouses. During the period of Japanese rule, it was even an important traffic route leading to Guanmiao. In this work, it is clear that Liao simplified the elements in the image to concentrate on the city gate and the everyday life of the locals. East Gate in Summer (fig. 5) by Sai Botatsu (Tsai Ma-Ta) adopted a side angle to look at the east gate from a distance. With a more careful arrangement to create visual depth, the dark tree shade, the figure resting in the shadow, and the ox all hinted at the sizzling summer heat while forming a serene corner quietly sitting away from the main road.

2. Temples

Among the paintings of the Tainan landscape from the 1st to the 5th Taiten, five of them featured the theme of temples or temple festivals. The depicted temples include Chiayi Tianhou Temple, Tainan Dongyue Temple, Beigang Chaotian Temple (fig. 8), Tainan’s God of War Temple, and Tainan Mazulou Tianhou Temple, which have all been important religious centers since the Ming and Qing dynasties. Meanwhile, the approaches of Eastern-style and Western-style paintings also varied greatly. For example, Jyo Seiren’s The View of a Spring Night (fig. 6) and Shi Yu-Shan’s Festival of Chaotian Temple (fig. 7) delineated the crowds at temple festivals and the lively atmosphere of such occasions. This is perhaps because the tradition of Eastern-style painting originated from that of the Yamato-e painting, which traditionally highlights the folk quality, the narrative, and distinctive compositional methods in a vivid manner. In comparison, the Western-style painting division of the Taiten, which mainly continued the Impressionist style, tends to show simplified forms.

【Fig. 6】

Jyo Seiren, The View of a Spring Night, 1928, the 2nd Taiten

Source: Catalogue of the 2nd Taiten

【Fig. 7】

Shi Yu-Shan, Festival of Chaotian Temple, 1929, the 3rd Taiten

Source: Catalogue of the 3rd Taiten

【Fig. 8】 The front view of Beigang Chaotian Temple published by Guoching Photography Studio in Tainan.

Source: National Museum of Taiwan History

Jyo Seiren’s The View of a Spring Night and Shi Yu-Shan’s Festival of Chaotian Temple both reveal an interesting composition to portray folk religious activities in the area of Tainan Prefecture. Due to the improvement of health care, transportation, and electric power, the function of temples as a site for worshipping deities also evolved accordingly. Festivities for welcoming deities and gods often attracted people from around Taiwan and became opportunities for selling products, thus injecting a lively commercial air into temple festivals. The Taiwan Nichi Nichi Shin Po wrote about a spectacular scene at Beigang Chaotian Temple:

Men and women from different villages came on pilgrimage and also visited the market for grocery shopping by the way, giving the market’s business a boost. It has been three years since the inauguration of Beigang Chaotian Temple. People no longer travel south. Recently, the shops in Tainan have faced a slump in business. So, an agreement is made to welcome the goddess from Beigang in March of the lunar calendar to restore the market’s business. Many people have agreed on the plan, and suitable representatives will be chosen to negotiate with the director and furnace owner in Beigang.

This passage shows the economic depression of Tainan at the time, which relied on joining religious activities of different regions to revitalize commerce. The two works brilliantly embodied the “local color,” juxtaposing modern and traditional characteristics. In particular, Shih was a self-taught artist, and his work displayed painting characteristics different from that of the Eastern-style painting division of the Taiten, which emphasized painting from life and realistic expression.

【Fig. 9】 Misono Nobuya, In Front of the Temple, 1928, the 2nd Taiten

Source: Catalogue of the 2nd Taiten

【Fig. 10】 The front view of Yue-Di Temple during the period of Japanese rule (probably after 1942)

Source: Database of the Ministry of Culture

【Fig. 11】 Liao Pao-Sung, Yuedi Temple, 1929, the 3rd Taiten

Source: Catalogue of the 3rd Taiten

【Fig. 12】 Kuo Po-Chuan, Alley in Front of Kuan Ti Temple, 1929, the 3rd Taiten

Source: Catalogue of the 3rd Taiten

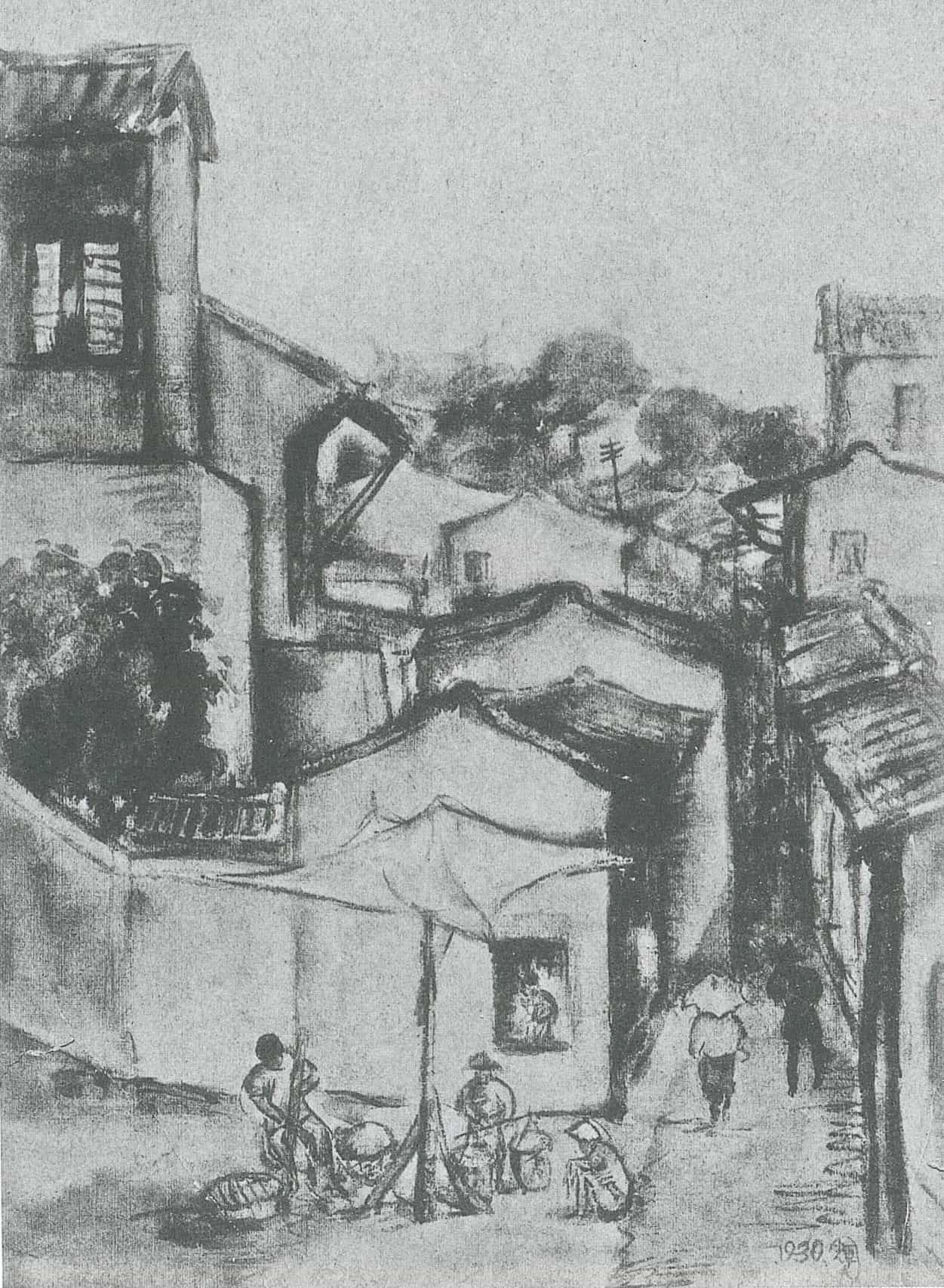

【Fig. 12】 Kyo Kin-Rin (Hsu Chin-Lin), The Temple in the Afternoon, 1930, the 4th Taiten

Source: Catalogue of the 4th Taiten

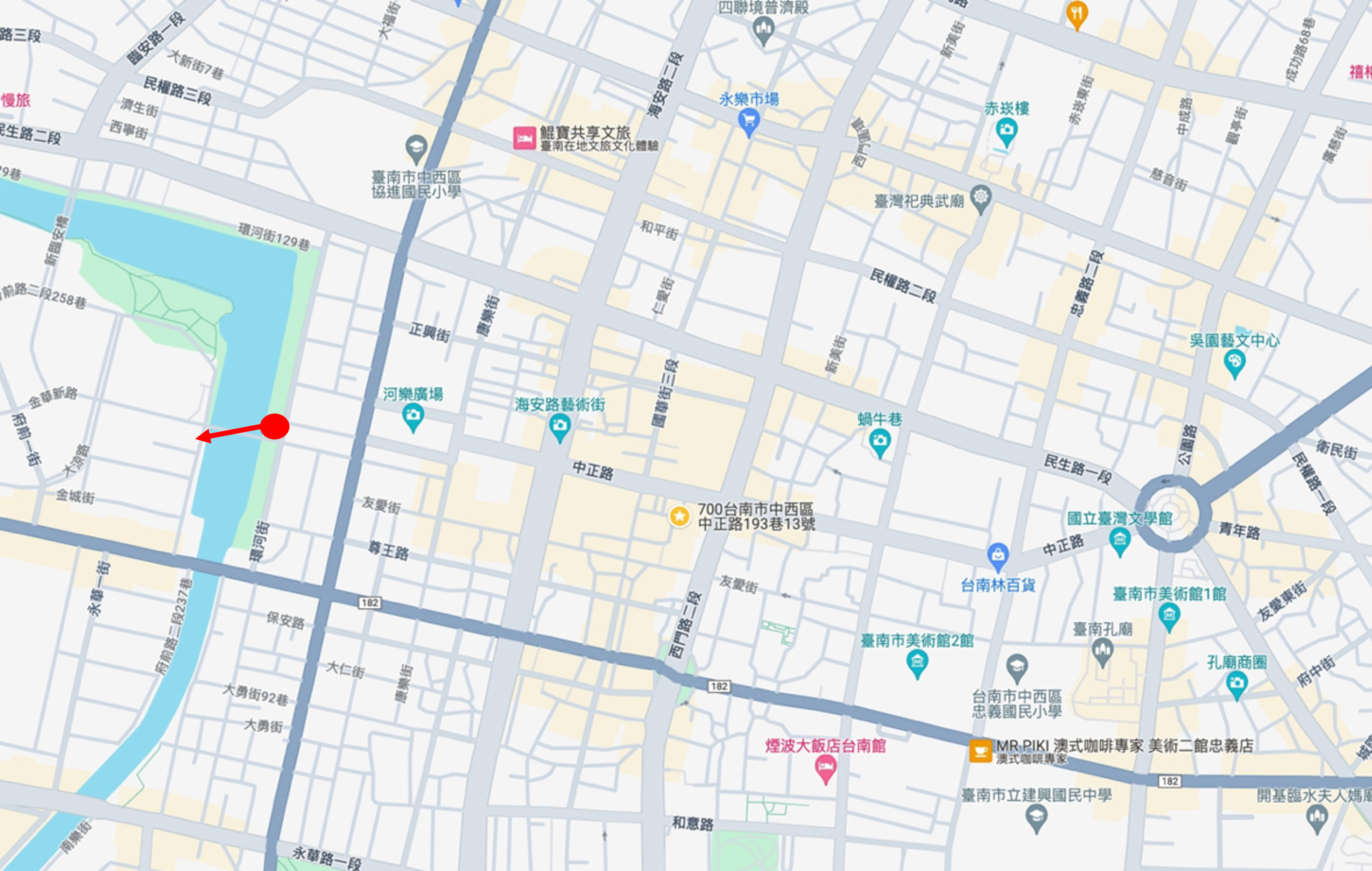

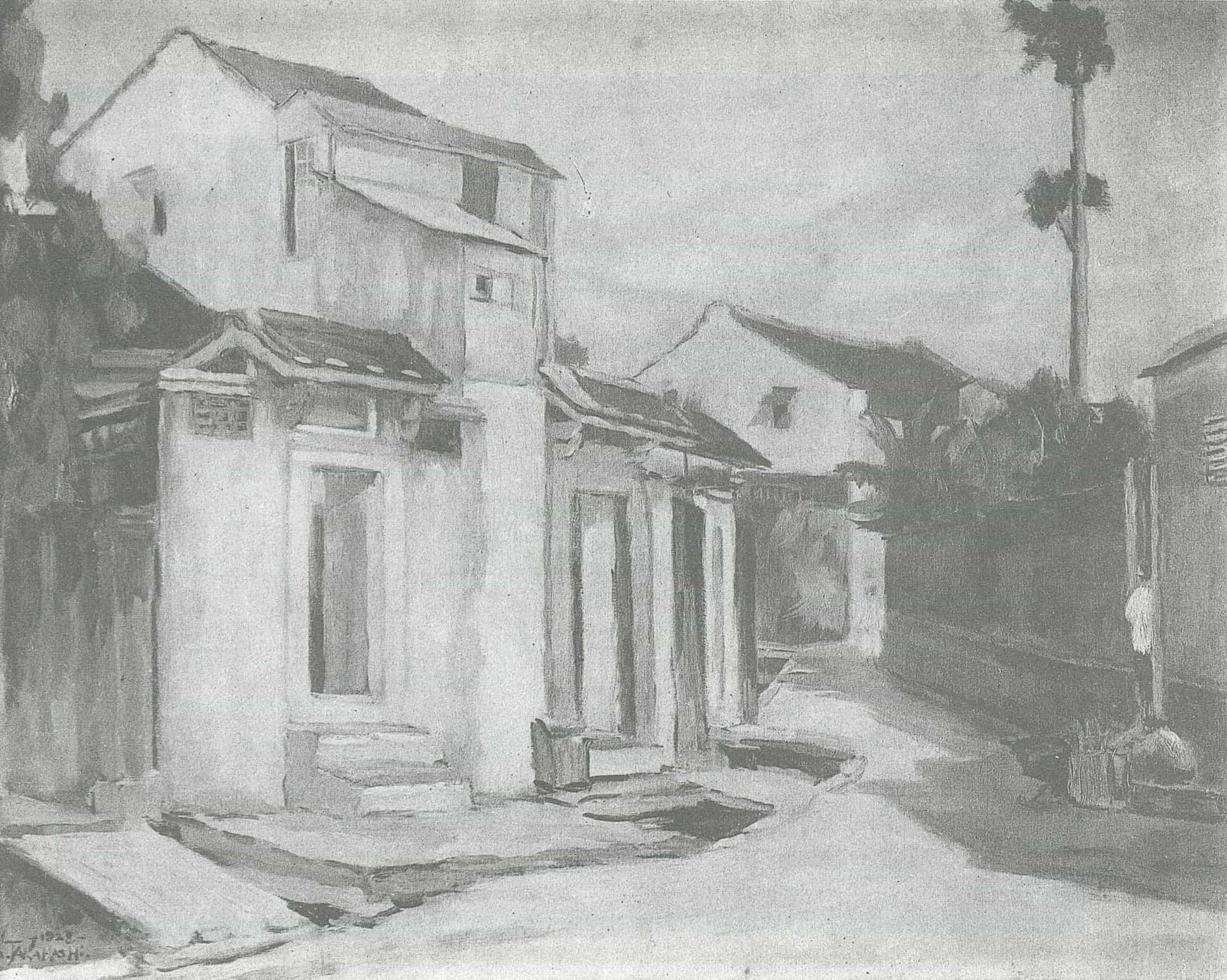

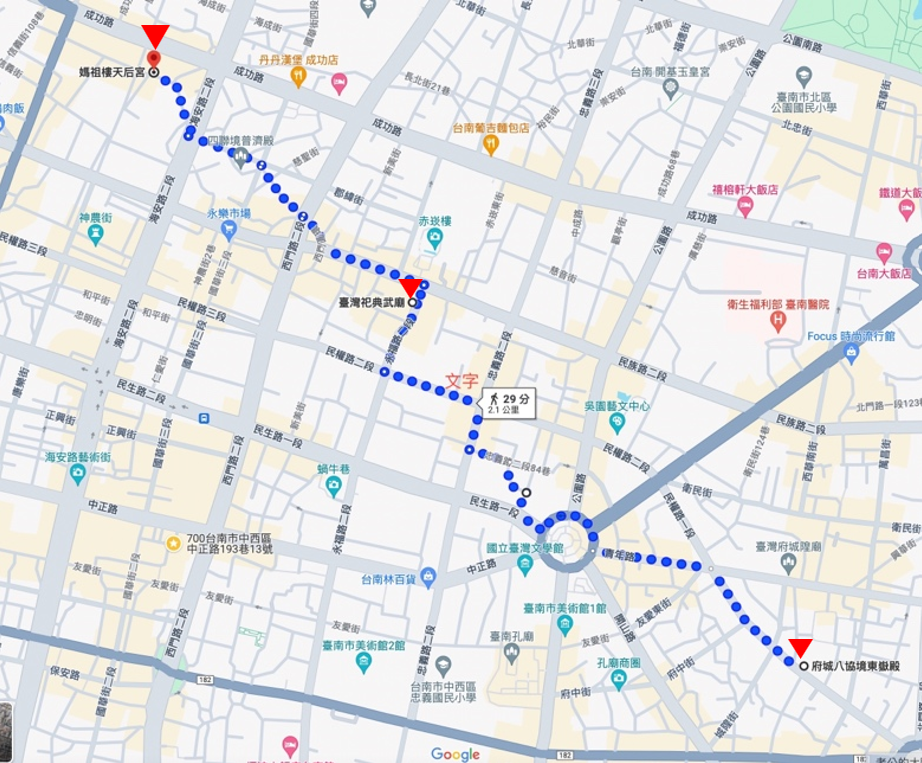

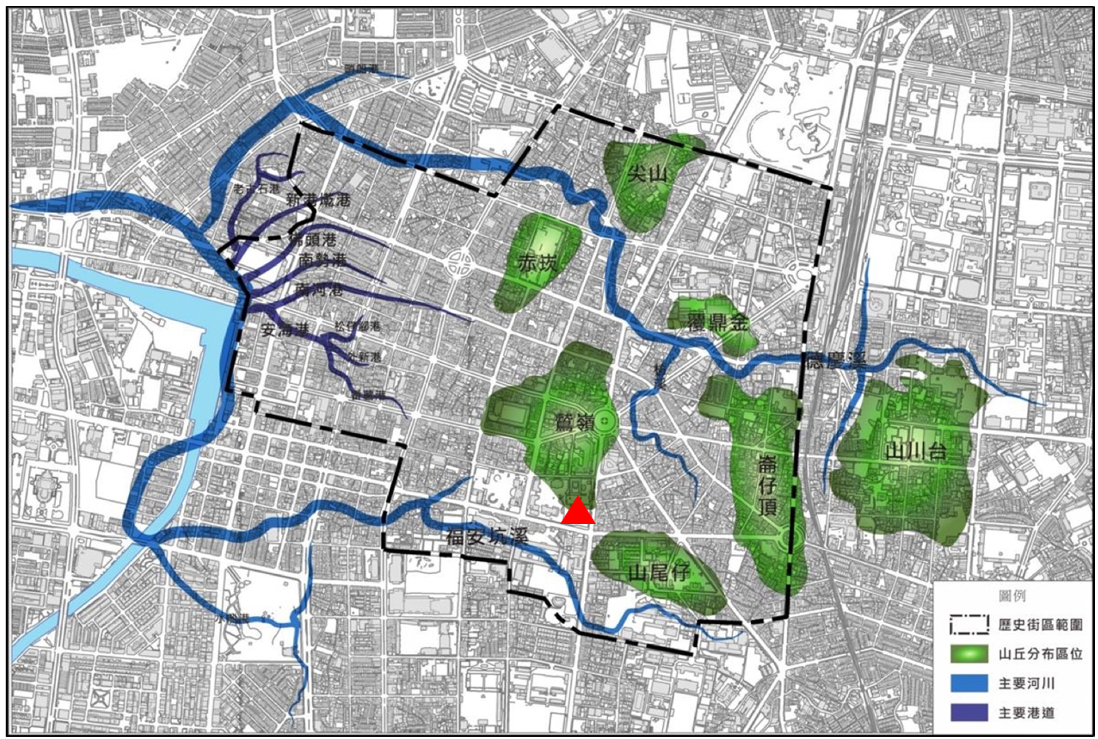

The charm of the local color that informed Eastern-style painting might better fit what Maruyama Banka described as “scenes.” In comparison, the Western-style paintings depicting temples exuded a stronger everyday ambiance and portrayed the subjects sitting quietly and solemnly on street corners. Liao Pao-Sung’s Yuedi Temple (fig. 11), Kuo Po-Chuan’s Alley in Front of Kuan Ti Temple (fig. 12), and The Temple in the Afternoon (fig. 13) by Kyo Kin-Rin (Hsu Chin-Lin) respectively delineated the God of War Temple, Mazulou Tianhou Temple, and Dongyue Temple today. Judging from the three temples’ locations, one can easily pass the temples when walking down Minquan Road toward the northeast. (fig. 14) A comparison with a map from the rule of the Qing dynasty (fig. 15), it clearly shows that the three temples are located in the intersecting area of Mingquan and Zhongyi roads. Since the Ming dynasty, this area was Tainan’s center, and after entering the Qing dynasty’s rule, the city’s development had followed the intersection and developed toward the east and the west, making it an important political and commercial center during the period of Qing rule. Today, when walking through the city’s streets and alleyways, one can always delightfully observe the subtle dynamics formed by the temples’ position and old houses in the city. Liao’s Yuedi Temple, Kuo’s Alley in Front of Kuan Ti Temple (fig. 12), and Kyo’s The Temple in the Afternoon all show a vertical arrangement accentuated by lines of houses in the composition. This is because the Mazulou Tianhou Temple and Dongyue Temple both sit east and face west, but houses of common people mostly sit south and face north. This difference has created the unique streetscapes of Tainan. Before the Qing dynasty, the eastern part of Tainan was a plateau, and the western part was mainly flatland, with an inner sea created by the Taijian area and off-coast sandbars. There were various rivers running from the east to the west, flowing into Taijian in both the north and the south (fig. 16). As time progressed and due to natural forces, the lagoons between Tainan and Anping gradually became land due to aggradation, leaving only a waterway leading to Anping from Wutiaogang outside the western part of Tainan.

【Fig. 14】 The current locations of Dongyue Temple, God of War Temple, and Mazulou Tianhou Temple

【Fig. 15】 Distribution Map of Historical street levels and locations (from the “Project Proposal of Tainan’s Historic Block” issued by the Cultural Affairs Bureau, Tainan City Government in 2017. The yellow areas are the locations of the three temples marked by the author).

【Fig. 16】 A sketch map of Tainan’s natural environment during the rule of the Qing dynasty (the red triangle marks the location of the Confucius Temple). The sketch map is taken from the “Project Proposal of Tainan’s Historic Block” issued by the Cultural Affairs Bureau, Tainan City Government in 2017.

3. The Confucius Temple and Others

【Fig. 17】 Chyo Gayu (Chao Ya-You), Red Gate, 1929, the 3rd Taiten

Source: Catalogue of the 3rd Taiten

【Fig. 18】 Entrance of the Confucius Temple in 1927.

Source: Digital Collections of the National Taiwan University Library

The Tainan Confucius Temple (fig. 18) has been an extremely popular subject among artists. Both artists from and not from Tainan often visited the temple to paint and create their idiosyncratic works. Since the Kingdom of Tungning, the Confucius Temple was the first school in Taiwan. During the period of Japanese rule, Japanese people also revered Confucius and renovated the temple, making it one of the cultural symbols of the city. Kawashima Riichiro and Fujishima Takeji were inspired by the architectural form and redbrick buildings of the Confucius Temple, which were said to evoke nostalgic sentiments. In the early period of Japanese rule, the temple was transformed from a site of religious rituals and education into a public school that mainly accepted Taiwanese students, first as the Tainan National Language Learning School and then the Tainan First Public School. In 1916, the Japanese government decided to renovate the Confucius Temple, and the renovation project encompassed various parts of the temple, including the Ta-Cheng Hall, the Ming-Lun Hall, the Wen-Chang Pavilion, the Ta-Cheng Gate, the Gate of Virtue, the Gate of Rites, and the Path of Righteousness, along with the temple’s brick walls, sod, stone pavement, and trees. Most of the important architectural components in this renovation project were “dismantled, recorded by drawing, and rebuilt according to the original looks.” So, the Confucius Temple painted by Chyo Gayu (Chao Ya-You) in Red Gate was already after the renovation. Chyo had deep feelings for the temple, which was obvious given the fact that he was the long-term president of the “Yi-Cheng Society” that aimed to bring back the court music of the Tainan Confucius Temple. He also wrote the article, titled “Research on the Sacred Temple,” which was a study of the temple’s historical context. Intriguingly, the Ta-Cheng Gate painted by Chyo in Red Gate (fig. 17) was situated at the highest ground in the image, showing a gently rising terrain. Compared to the topographic map from the Qing dynasty, it can be seen that the Confucius Temple was located at the foot of Eagle Hill (fig. 16), sitting north and facing south. Although the terrain had grown increasingly flat after the Japanese rule, signs of a rolling terrain still remain. The painter delineated and represented what he saw through his work, fully demonstrating his understanding of the temple’s architecture and terrain.

【Fig. 19】 Hara Susumu, Early Spring, 1927, the 1st Taiten

Source: Catalogue of the 1st Taiten

【Fig. 20】 The Tainan Theological College and Seminary in the 1930s.

Source: Digital Collections of the National Taiwan University Library

【Fig. 21】 Takei Shyoichi, In the Forest, 1928, the 2nd Taiten

Source: Catalogue of the 2nd Taiten

Hara Susumu’s Early Spring (fig. 19) and Takei Shyoichi’s In the Forest (fig. 21), on the other hand, portrayed a place characterized by a Western exotic air during the period of Japanese rule, where painters often visited for painting. The Tainan Theological College and Seminary (fig. 20) depicted by Hara was an important location where James Maxwell carried out missionary work since 1865. In 1876, Dr. Thomas Barclay combined the “Communicant’s Class” and the “Student’s Class” before establishing the Capital College, which became the first Western-style college in Taiwan. The current buildings of the college and seminary were only built during the period of Japanese rule (1903). In 1913, the college was renamed the Tainan Theological College and Seminary. In Hara’s painting, the withered branches convey the imagery of early spring, and the brisk and lucid color planes somehow add a bleak feeling. Located outside the city’s border, the college and seminary seem especially secluded and quiet. The Anping Customs House in Takei’s In the Forest was also located outside the city. Originally built in 1882, it was relocated to Fort Zeelandia (now Anping Old Fort) in 1897, and was later made a rest area in 1929. Perhaps it was because its location was not within the historical street blocks throughout the two regimes, people rarely visited the area of Anping, and even fewer painters went there for painting. When touring through the area, Kawashima Riichiro gave the following description about Anping:

One could take the bus to Anping, but taking the old-style handcars was more interesting…Sitting on the sliding handcar while watching the boats sailing on the canal was like escaping modern times…When Anping was in sight, one did not feel like entering the city streets…The level of dilapidation was surprising…The residential houses in the vicinity were all broken and ruin-like…When I first arrived in Anping, the sight reminded me of the ruins of Ostia (the outer port of ancient Rome) from the peak of the seaport of ancient Rome.

This passage paints a desolate picture of Anping. However, in the eye of the Japanese artist, the ruinous landscape exuded a classical, romanticist quality characteristic of Tainan and evoked a local view informed by nostalgic sentiments.

(II) Sensibility-based Experiences in Modern Life: Roundabouts, Parks, Streets, and Canals

The early modern construction of infrastructure during the period of Japanese rule, such as parks, roundabouts, department stores, cinemas, and canals, offered people venues for everyday activities and entertainment. Because the Taiten advocated the “local color,” painters included these attractions in their works and combined the Western approach of painting from life and the technique of perspective, making these sights new topics in the government-funded art exhibitions.

Tainan City has the largest number of roundabouts in Taiwan. The construction of roundabouts, which offered locals leisure spots, was influenced by the urban planning of Paris in the 19th century. Meanwhile, the Anping Canal inaugurated in 1926 carried the memories of a busy seaport. Painters often strolled along the riverbanks and painted the heterogeneous sights created by the coexistence of the southern air and modern construction. An example is Anping Canal by Ko Kin-Kan (Kao Chun-Chien). Another one is Yokoyama Fumiko’s Tainan Ginza at Sunset, which delineates a nightlife scene different from the landscape under bright daylight. Compared to the delineation of historical sites in the ancient city, which tends to follow a certain viewpoint and paradigmatic composition, modern landscapes reveal more diversified expression. The streetscape, easily gleaned in everyday life, represents moments of sensibility experienced by artists when walking through the city. This section discusses the topics of modern infrastructure during the period of Japanese rule, which includes “canals,” “streets,” as well as “parks and others.”

1. Canals

Before the period of Japanese rule, foreign trade already flourished in Tainan, and consulates of different countries were established in Anping. The Old Canal began from behind the air force hospital on Anping Road and extended along the current highway into Anping Harbor. This canal, now known as the Old Canal, split into five sub-canals that flowed through the city, which became known as “Wutiaogang.” In 1903, due to the changing course of Zhengwen River and its deposition of silts, the canals were gradually covered. The Tainan Canal, located to the west of the Old Canal, was excavated in 1922 and completed in 1926, and the 1st to the 5th editions of the Taiten were held from 1927 to 1931. The newly inaugurated canal might be the reason why there were so many works depicting the Tainan Canal throughout the five editions of the Taiten.

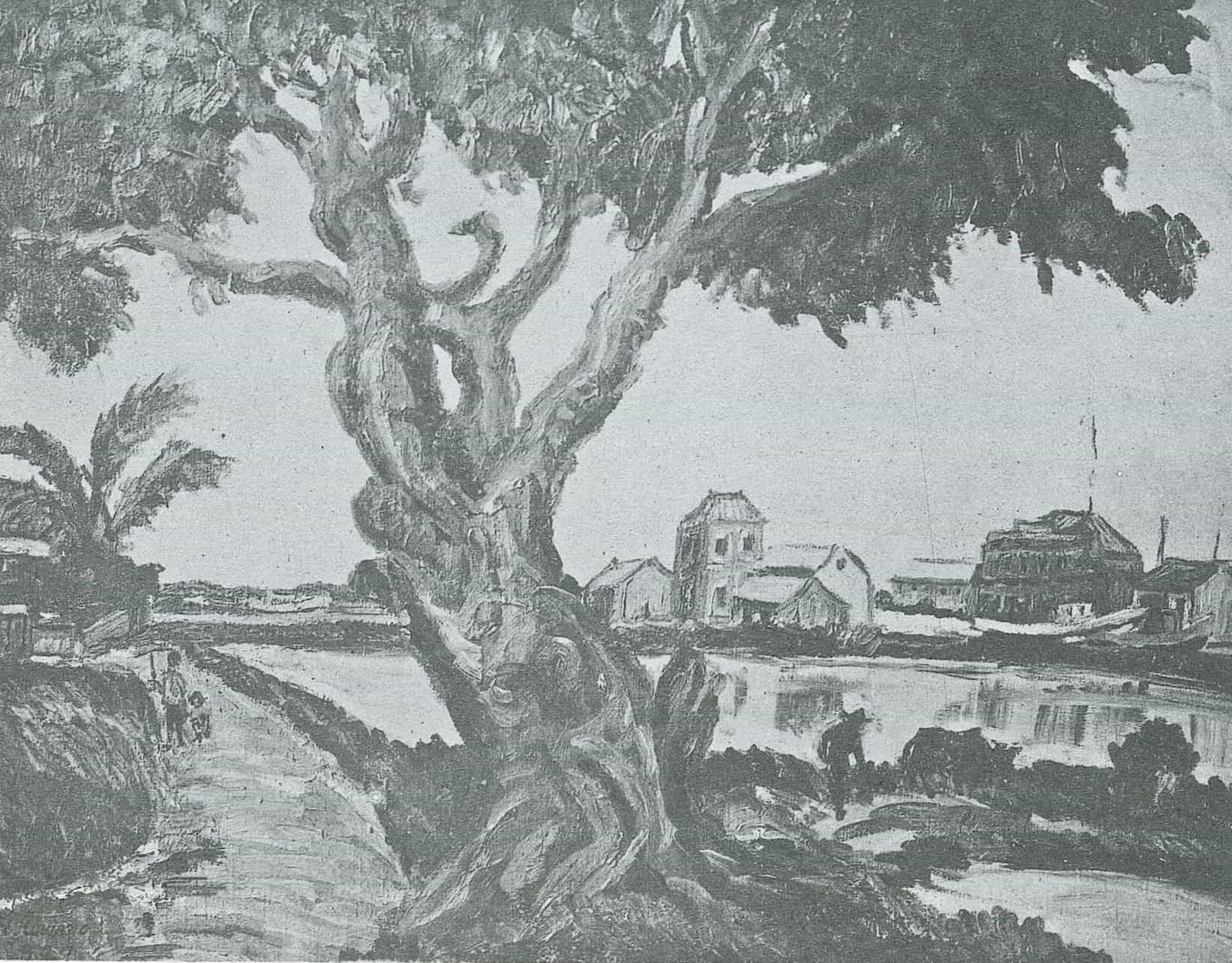

【Fig. 22】 Kuwano Ryokiti, The Canal with a Marabutan, 1927, the 1st Taiten

Source: Catalogue of the 1st Taiten

【Fig. 23】 The Tainan Canal during the period of Japanese rule.

Source: Digital Collections of the National Taiwan University Library

【Fig. 24】 Ko Kin-Kan (Kao Chun-Chien), The Tainan Canal in the Morning, 1929, the 3rd Taiten

Source: Catalogue of the 3rd Taiten

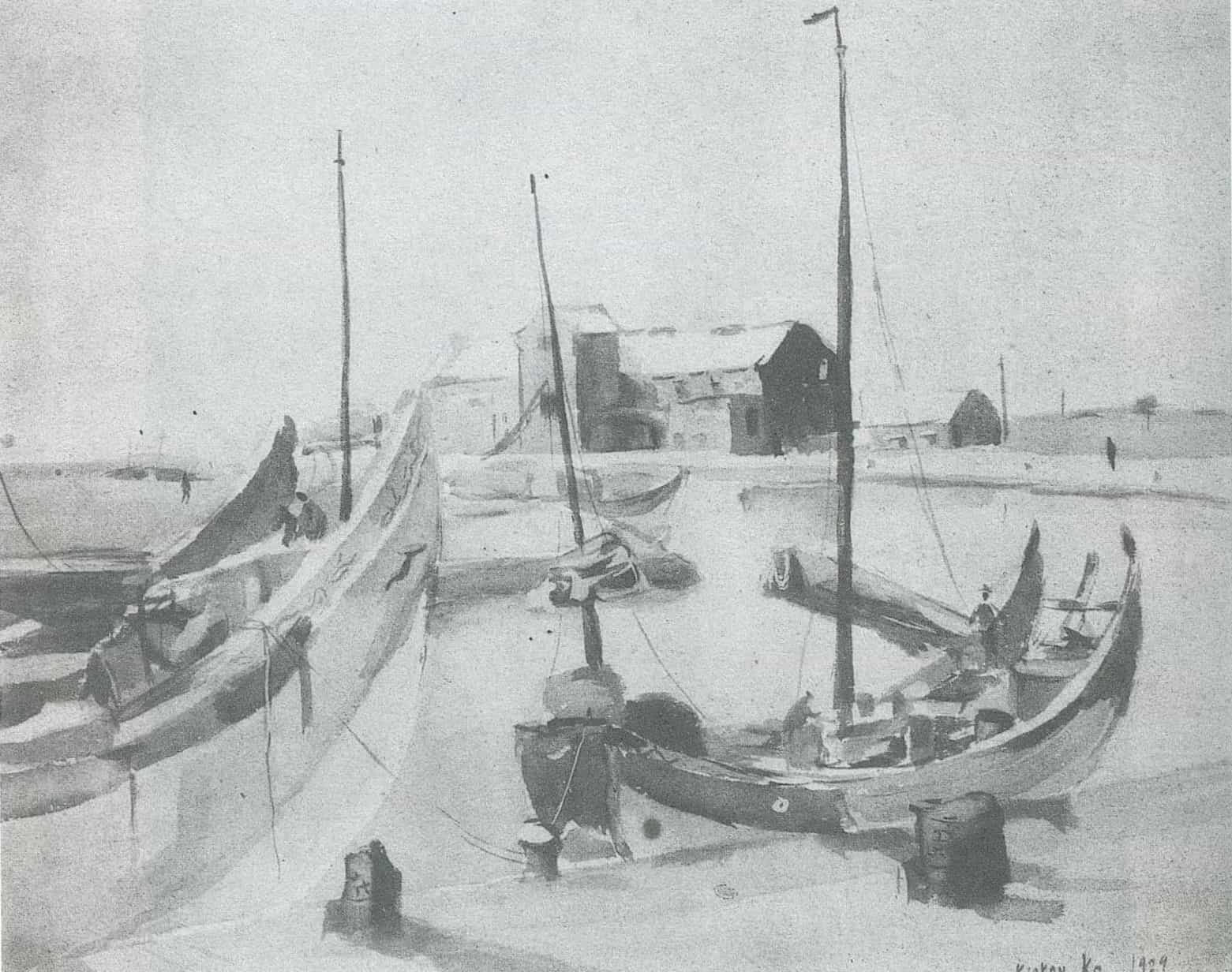

【Fig. 25】 Kuwano Ryokiti, Wharf, 1930, the 4th Taiten

Source: Catalogue of the 4th Taiten

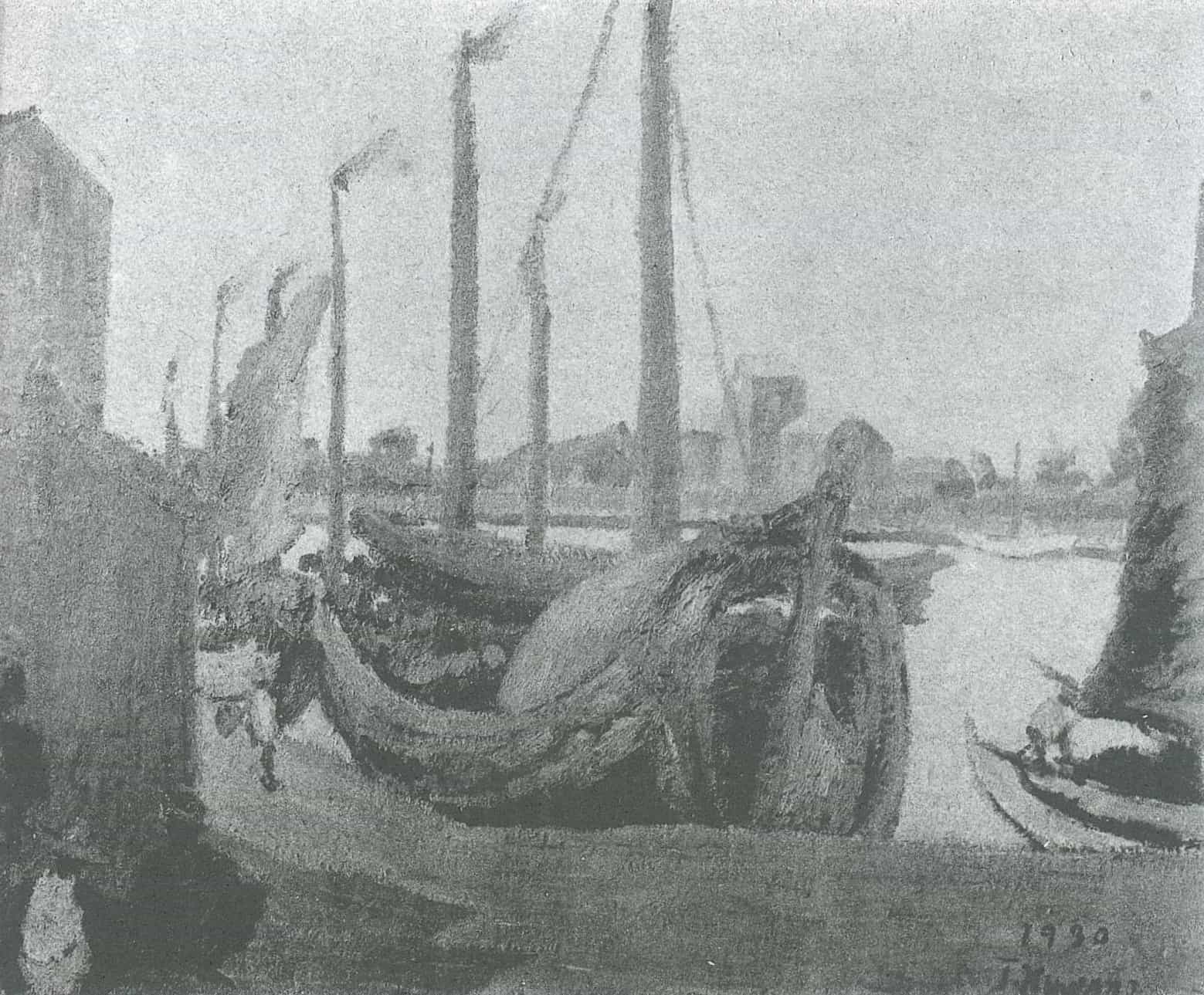

【Fig. 26】 Nashima Mitsugi, The Junks, 1930, the 4th Taiten

Source: Catalogue of the 4th Taiten

【Fig. 27】 Misono Nobuya, Sunset on the Canal, 1930, the 4th Taiten

Source: Catalogue of the 4th Taiten

A general review of the works depicting the Tainan Canal and the streets shared a similar composition. In the distant background, factory buildings can be seen where the ships docked. They were the Tainan Second Factory of the Great Japan Ice Co., Ltd., together with the Taiwan Sugar Industry Co., Ltd. and the fish market in the vicinity. The wharf across these factories was located at the end of the modern-day Zhongzhen Road. This spot was where the painters stood when making paintings (fig. 28 & 29). Except for Misono Nobuya, other painters mentioned above depicted the factory buildings, making them iconic landmarks. The dense number of Junk ships docking on the wharf also created a prosperous atmosphere for the fishing port. The new canal, which was completed in 1926, boosted fish transportation and sales while facilitating the rise of the entertainment business, such as cinemas, and increasing the number of leisurely sites where the locals could take walks and have excursions. The traditional opera production A Surprising Case along Tainan Canal in the 1930s and the film The Canal Suicides directed by Ho Ming-Chi in 1956 were both based on real events involving the Tainan Canal, showing how strongly the canal was appealing to people’s sensibility.

【Fig. 28】 The artist’s viewpoint when painting from life on the wharf.

【Fig. 29】 An old photograph of the wharf on the Tainan Canal.

Source: Bureau of Tourism, Tainan City Government

2. Streets

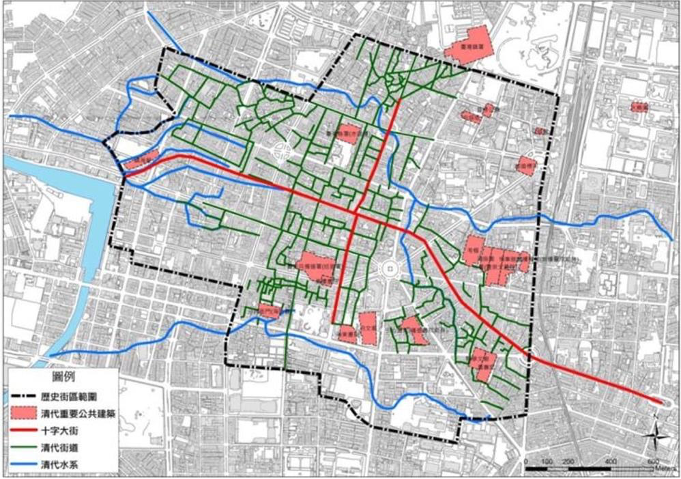

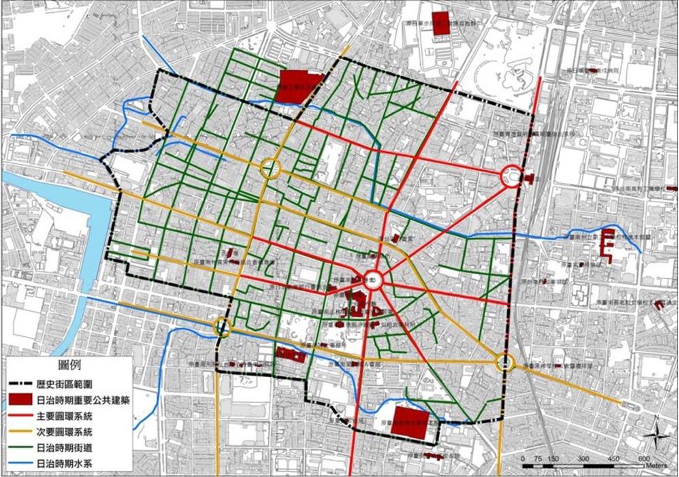

An important part of Taiwan’s modernization was the urban planning project implemented during the period of Japanese rule. Based on what is shown in fig. 30 and 31, the urban construction in the period of Japanese rule was built upon the road system from the Qing dynasty to expand existing roads while expanding them into seven main roads, using the roundabout of the Taisho Park (now Tang Te-Chang Memorial Park) as the center to replace the large intersectional area from the Qing dynasty. From streets marked green in the image, it can be seen that the smaller roads were straightened during the period of Japanese rule and the street blocks were divided based on a checkerboard pattern while the winding, irregular urban texture comprising lanes and alleyways from the Qing dynasty were also preserved. This created the current cityscape in which old and new houses and streets are intermixed, forming a complicated yet rather unique street system and increasing the diversity dissimilar from that of modern European cities.

【Fig. 30】 Diagram of the urban structure during the Qing dynasty

taken from the “Project Proposal of Tainan’s Historic Block” issued by the Cultural Affairs Bureau, Tainan City Government in 2017.

【Fig. 31】 Diagram of the urban structure during the Japanese rule;

taken from the “Project Proposal of Tainan’s Historic Block” issued by the Cultural Affairs Bureau, Tainan City Government in 2017.

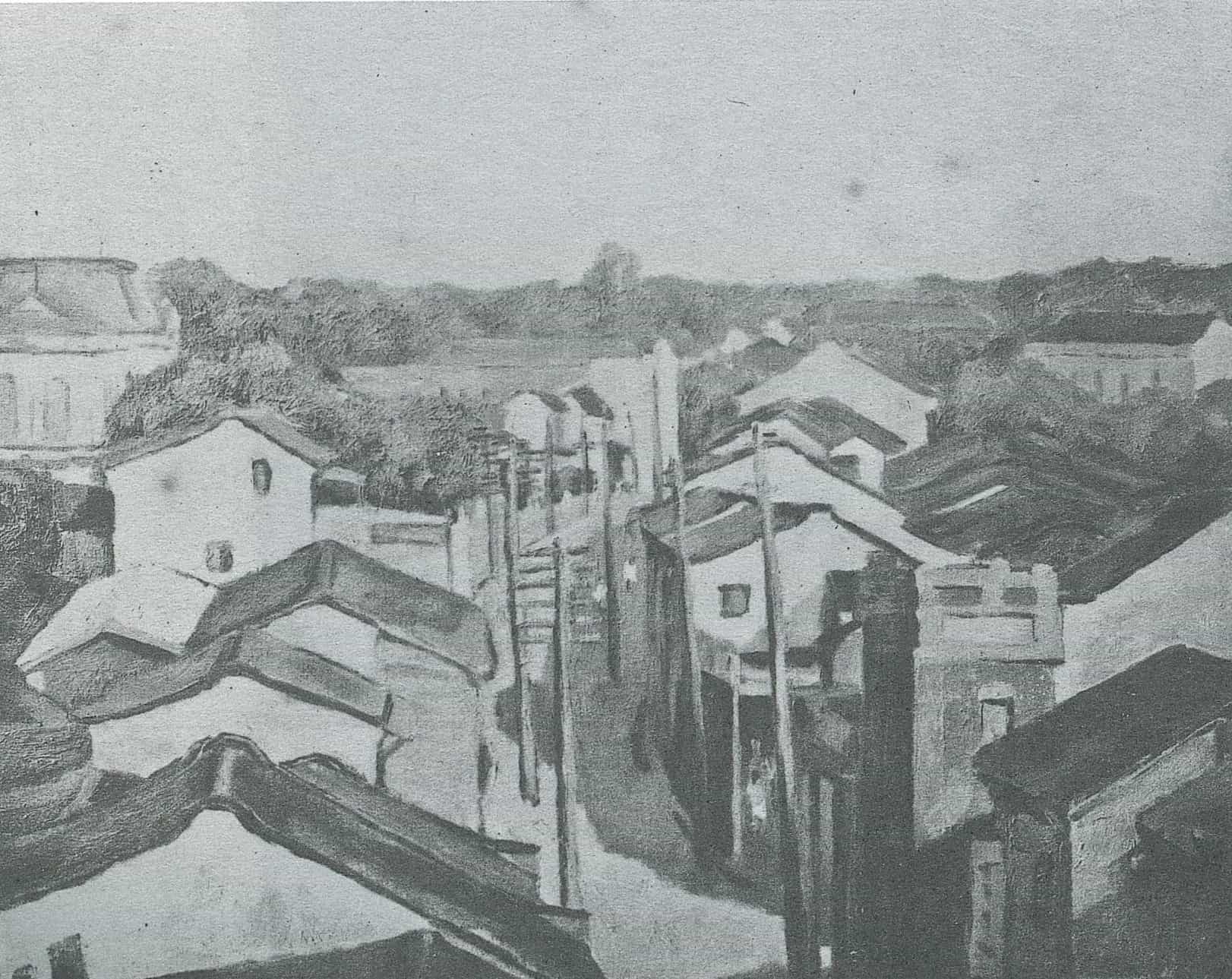

Among the landscapes of street scenes selected from the 1st to the 5th Taiten, apart from Takahashi Kiyoshi’s Tainan in September (fig. 32), of which the location remains unidentified, Liao Chi-Chu’s work delineated the main road whereas the works of Chen Ken-Chin, Oshimoto Teruo, and Takahashi also portrayed alleyways (fig. 34 & 36). In Japanese, “uramachi” refers to the street blocks not adjacent to big roads and located on small alleys. These works of the painters documented the common scenes in everyday life. Chen’s Back Street (fig. 33) delineates the everyday scene of laundry hung up to dry in an alley, forming an interesting contrast to the Shuixian Temple (水仙宮) in the background. In the same year, Ishikawa Kinichiro’s A Temple in Tainan also depicted the same subject but without the utility pole included in Chen’s work. Oshimoto, on the other hand, depicted the intersection of Qingnian Road and Minquan Road, showing street vendors gathering in the street corner. The building stretching upward on the left side was presumably the neighboring house next to Dr. Sen-Yu’s residence in Shimizu-cho. On the right was the Takasago-cho, which was located east of the 1st section of Minquan Road. This work depicted the location same as Liao Chi-Chun’s Street (fig. 35). The difference was that Oshimoto portrayed the narrow, crowded view of the alleyway through the one-point perspective, whereas Liao delineated the expansive, busy intersection of the two roads with the advertisement board and bustling crowds on the street, vividly contrasting the publicness of the road and the privateness of the back alley.

【Fig. 32】Takahashi Kiyoshi, Tainan in September, 1927, the 1st Taiten

Source: Catalogue of the 1st Taiten

【Fig. 33】Chen Ken-Chin, Back Street, 1927, the 1st Taiten

Source: Catalogue of the 1st Taiten

【Fig. 34】 Takahashi Kiyoshi, Backstreet, 1928, the 2nd Taiten

Source: Catalogue of the 2nd Taiten

【Fig. 35】 Liao Chi-Chun, Street, 1928, the 2nd Taiten

Source: Catalogue of the 2nd Taiten

【Fig. 35】 Oshimoto Teruo, A Backstreet in Tainan, 1930, the 4th Taiten

Source: Catalogue of the 4th Taiten

These works featuring the streetscape were all painted in the plein-air style, which was rather common in the Taiten. However, the serene street scenes and simple life of ordinary people depicted in these paintings showcased by the Taiten reveal a reality drastically different from the one described by contemporaneous literary writers. In Sheng Kai’s “Back Street Life: The Back Street Scenes in the Artistic and Literature Works during the Japanese Colonial Period,” the author quoted a passage from Lung Ying-Tsong’s short story, “A Town of Papaya Trees” (1937):

Walking on the dried, cracked road, hot sweat dripped from my face. The streets were filthy and dark. The bases of utility poles were darkened…Entering the lane, the joined houses looked even dirtier in the back street, with weathered, dilapidated mudbrick walls…The narrow lane was wet, and the stench from children’s openly urinating and defecating mixed and rose with evaporating heat.

As the passage shows, the gloominess, filth, and stench seem to form a realistic depiction of the back streets, yet these elements of uncleanliness are absent in the landscape paintings. Such an aesthetic attitude of the artists, informed by a flaneur state of mind and simple intuition, differed from Baudelaire’s aestheticism. One could say that these works featuring the back streets only share the “appearance” but not the “essence” with Western impressionism. The work of the Japanese painter Takahashi Kiyoshi unveils an empty, desolate street view composed of vertical lines and seems to emphasize the atmosphere. In an interview published in the newspaper column “A Studio Tour of the Taiten,” a comment was given about the painting: “on the one hand, the work is influenced by the orthodox painting style of Suzuki, and on the other hand, it shows the unorthodox charm of the Nankosha, which is characterized by clever composition and vibrant colors.”

3. Parks and Others

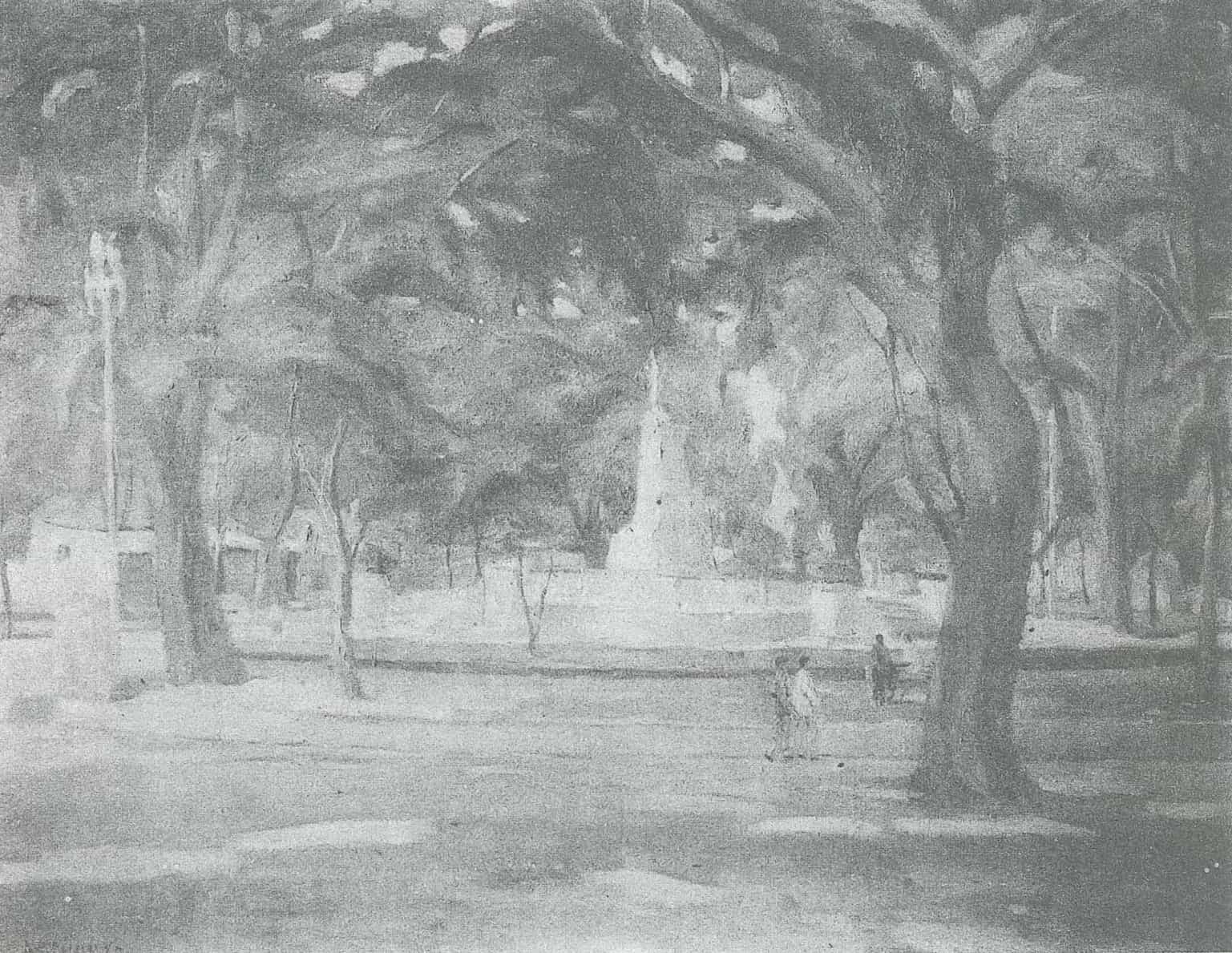

After discussing Tainan’s back streets, what different interpretations did the painters have for the city center and main roads? Among the works depicting the subject of parks from the 1st to the 5th Taiten, Liao Chi-Chun and Takahashi Kiyoshi delineated the Taisho Park, which is now the Tang Te-Chang Memorial Park (fig. 37). As the central administration area during the period of Japanese rule, the roundabout was right across the Tainan Prefectural Hall, connecting seven traffic arteries. Following the roads, one will pass the Tainan Police Department (now Building 1 of the Tainan Art Museum), the Tainan He Tong Building (now Tainan City Fire Museum), the Tainan Public Hall (now Wu Family Garden), the Tainan Confucius Temple, the Forest Office (now Yeh-Shyr-Tau Literary Memorial Museum), the Tai Peng Keng Maxwell Memorial Church, the Hayashi Department Store, the Kiong-kóo-tsō Theatre (now Wonderful Theatre, etc., which could be a political, economic, educational, and entertainment center. This location was the former residence of Lin Chao-Ying, which was turned into fire protection land and converted into a roundabout and green land in 1911 during the construction of urban planning (fig. 38). In Liao’s painting of 1929, the statute of Kodama Gentaro, the former Governor-General of Taiwan, stood at the center of the roundabout. Figures can be seen strolling in the green garden, which was partially covered by the trees, forming a sense of visual depth. Also selected for the 3rd Taiten, Takahashi’s Lebbek (fig. 39) showed a verdant scenery to form a vivid contrast. The statue, on the other hand, was entirely hidden in sight, and only the plinth was comparatively visible.

【Fig. 37】 Liao Chi-Chun, Early Summer, 1929, the 3rd Taiten

Source: Catalogue of the 3rd Taiten

【Fig. 38】 A postcard showing the image of the Taisho Park during the initial period of the urban planning project.

Source: Digital Collections of the National Taiwan University Library

【Fig. 39】 Takahashi Kiyoshi, Lebbek, 1929, the 3rd Taiten

Source: Catalogue of the 3rd Taiten

Liao lived briefly in Tainan from 1927 to 1936, but was selected for the Taiten and the Futen with twelve paintings featuring Tainan’s landscapes. In the 6th Taiten, he was again selected with a painting depicting the Taisho Park (fig. 40 & 41). This work placed the statute at the center of the image and portrayed the roundabout with a symmetrical arrangement, fully demonstrating Liao’s love for Tainan’s landscape. Furthermore, his compositional experiments with Taisho Park also visualize a certain gaze of multiple reflections informed by colonial legitimacy.

【Fig. 40】 Liao Chi-Chun, Green Shade, 1932, the 6th Taiten

Source: Catalogue of the 6th Taiten

【Fig. 41】 Liao Chi-Chun, Market, 1929, the 3rd Taiten

Source: Catalogue of the 3rd Taiten

Another landscape portraying a rare subject in the Taiten was Liao Chi-Chun’s depiction of the East Market. Close to Taisho Park, Tainan City’s Dong Cai Shih Public Market was located in the area of “Jingtingkou Street,” which was densely populated in the Qing dynasty. Because it was near Yuedi Temple and the City God Temple, fishmongers and butchers would gather in this area. During the period of Japanese rule, considering citizens’ need for livelihood and the convenience of grocery shopping, the Tainan mayor at the time chose the “Third Yuan Hui Jing Street Market” near Jingtingkou Street to be the “Tainan Market Extension Market.” In 1909, the “East Market” was built behind Dongyue Temple as the second modern public market after the West Market. Liao Chi-Chun lived near this area in the 1920s, so it was probably one of his most familiar places. In this work, the trees in the foreground divide the image into two halves. Both this work and Scene with Coconut Trees, which was selected for the Teiten (Japanese Imperial Art Exhibition) in 1931, have adopted a bold approach to composition.

IV. Conclusion

The 1st to the 5th Taiten could be said to be the beginning of Taiwan’s government-funded art exhibition. In this study of Tainan-themed landscapes, it is clear that the topics and composition of works that depicted modern infrastructure and facilities highly overlapped, e.g., the Tainan Canal and the streets in Tainan. Perhaps this is because Taiwanese artists were beginning to explore and formulate their own style. Or maybe the “local color” and a certain power-informed perspective restricted the Tainan-based artists. In comparison, the “historical scenes” portrayed by artists from the Tainan Prefecture have revealed a vivid diversity: on the one hand, some of the works featuring historical scenes were painted by Japanese artists, who focused on relations between figures, festivals, and sceneries. Their style was similar to that of custom or narrative paintings, which contributed to their works’ strong local color and charm. On the other hand, there was a higher percentage of Taiwanese and Japanese artists who painted historical scenes than that of artists who painted modern sceneries. These local artists, such as Kuo Po-Chuan, Lin Yu-Shan, Sai Botatsu (Tsai Ma-Ta), and Chyo Gayu (Chao Ya-You), grew up in Tainan Prefecture, and the local landscape was surely more familiar and attractive to them due to their travels and experiences. An example would be Chao’s “Research on the Sacred Temple,” which shows his deep connection with the Confucius Temple. Therefore, the first chapter of this study – “The Past and Present of an Ancient City and Its Historical Sites: the Confucius Temple, City Gates, the Theological College and Seminary, and Other Temples,” compared to Maruyama Banka’s interpretation of historical scenes and lyrical scenes, argues that the former serves as the “appearance” whereas the latter is the “essence.” On the other hand, Ishikawa Kinichiro’s comparing Tainan to the Rome of Taiwan indicates the “historical scenes” in the eyes of a traveler.

“Sensibility-based Experiences in Modern Life: Roundabouts, Parks, Streets, and Canals,” however, underlines the common landscape paradigms in relation to image arrangement. These include works by the artists influenced by the teaching of Ishikawa Kinichiro (e.g., Chen Keng-Chin) and the first Taiwanese oil painting to be selected for the Teiten – Chen Cheng-Po’s Outside Chiayi Street (1926). Aligned utility poles and the straight street delineated using the technique of perspective became elements frequently employed in the paintings of street scenes that were selected for the Taiten. An example is Chen Keng-Chin’s Back Street. In terms of the subject of roundabouts and parks, the artists often used trees to create a sense of depth through the arrangement of the foreground and the background, for instance, Liao Chi-Chun’s Early Summer and Shimada Kiyoyasu’s Street Trees and Western-style Building. Although painting topics or available sceneries increased extensively during the period of Japanese rule, the expressive approaches were rather unvaried. A general review of the Tainan-themed landscapes from the 6th to the 10th Taiten shows that more works have portrayed the Confucius Temple and other temples. This might be due to the fact that the subject of temples is closely associated with local religious beliefs and people’s everyday lives while also echoing Japanese artists’ preference for the “local color.” When reminiscing about Taiwan’s scenery, Ishikawa Kinichiro wrote:

I most frequently traveled from the late Meiji period to the early Taisho period. In retrospect, it was a time when modernization had not yet begun, and the Taiwanese scenery was rather pure and simple. Particularly, Tainan at that time shared an ancient visage reminiscent of Nara or Rome…As of today, there is already no such characteristic landscape in Taiwan…This is the trend of the times, and there is nothing to be done about it.

In order to preserve the sceneries of historical monuments in Tainan, Hachiya Akira painted the God of War Temple, the Guan Yin Temple, the Confucius Temple, and the south gate, mentioning that “Tainan is the historical and cultural center of Taiwan. Now, modern civilization is damaging the old culture with a massive power to carry out comprehensive construction. This is about to destroy and wipe out the architectural legacies in various locations and of the indigenous people.” Judging from this passage, it can be inferred that the imagination of the historical city by the people at the time was shaped by Tainan’s historical monuments and temples. The characteristic modernity and flânerie embodied by the Tainan-themed landscapes probably became the artists’ familiar, understated, and ordinary everyday life as they wandered in the city’s historical sites and sacred temples.

1. 丸山晚霞,〈我所見過的臺灣風景〉,《臺灣時報》(1931年8月),第9版。

2. 李書旆,〈日治時期臺府展圖錄中的臺南風景畫研究〉計畫成果,臺灣藝術田野工作站。

3. 李書旆,〈日治時期臺府展圖錄中的臺南風景畫研究〉計畫成果,臺灣藝術田野工作站。

4. 西岡塘翠,〈說苑/島を彩れる美術の秋〉,《臺灣時報》(1927年12月)。

5. N生記,〈第四回臺展觀後記七〉,《臺日報》(1930年11月13日),第6版。

6. 陳秀蓉,〈日治時期臺灣民間信仰的發展〉,《歷史教育》第三期(1998年6月),頁151。

7. 《臺灣日日新報》(1913年3月29日)

8. 臺南市政府文化局,〈臺南市政府歷史街區計畫書〉,2017,https://culture.tainan.gov.tw/df_ufiles/060/臺南市府城歷史街區計畫書.pdf。

9. 臺南市政府文化局,〈臺南市政府歷史街區計畫書〉,2017,https://culture.tainan.gov.tw/df_ufiles/060/臺南市府城歷史街區計畫書.pdf。

10. 川島理一郎,〈臺南、安平風物記 臺灣紀行之二〉、藤島武二,〈映入藝眼中的臺灣風物詩——藤島畫伯談繪畫之旅〉,收入顏娟英譯著,《風景心境》,臺北市:雄獅,2001。

11. 高凱俊,《大臺南文化資產叢書02 臺南孔子廟》,臺南市:臺南市政府,2015。

12. 川島理一郎,〈臺南、安平風物記 臺灣紀行之二〉,收入顏娟英譯著,《風景心境》,臺北市:雄獅,2001,頁82。

13. 蘇恩恩編,《悠活臺南 臺南市刊》第37期( 2020年秋季號),頁15。

14. 林咏榮,〈臺南古運河〉,《臺南文化》第3卷第4期( 1954年4月30日),頁18。

15. 此作曾刊載於《臺灣日日新報》(1927年)中的石川欽一郎「臺灣的羅馬」專欄,描繪主題包含大南門、萬壽宮、臨水夫人廟,以及本作的水仙宮巷弄一景,可一窺日人對於臺南風景的喜好與構圖方式。

16. 龍瑛宗,《植有木瓜樹的小鎮》,臺北市:遠流,1997,頁5。

17. 盛鎧,〈裏町人生——臺灣日治時期美術與文學的後街風貌〉,《臺灣美術》第85期,頁18-19。

18. 〈アマチュアの繪赤樓を描く―高橋漬、朝の洗濯―藍蔭鼎〉,《臺灣日日新報》(1927年10月5日),第7版。

19. 鷗亭生第六回臺展時曾評審查員廖繼春的兩件作品《高雄風景》與《綠蔭》:「與其說技巧或色彩好,不如說是因為巧妙地選對可以入畫的地方,換言之,就是他的眼光及構思很好。陽光燦強而燦爛的南臺灣風光,竟能以如此沈穩的色調來表現,正是其特色吧!…其構思及構圖最為引人注目,在臺展中自成一格,令人欣喜。」文中顯現其作品描繪的地點與構圖符合了評論者所好。引自鷗亭生,〈第六回臺展之印象〉,《臺日報》(1932年10月26日至11月3日)。

20. 石川欽一郎,〈臺灣風光的回想〉,《臺灣時報》(1935年6月)。

21. 蜂谷彬,〈繪畫旅行通信〉,《臺灣日日新報》(1917年3月8日)。

作者

周歆,畢業於國立臺南藝術大學藝術史學系暨藝術史評與古物研究所碩士班,現任職於富邦美術館。主要研究領域為臺灣美術史、地方美術史。畢業論文為《主流藝術外的初聲——阿普畫廊的前衛性研究》,以畫廊一手資料建置以及90年代定位之探究為主。近年曾參與多項地方美術史研究如:《隱微的幽光:新竹市典藏研究專刊》(2023)、「考現地方:臺南美術資料庫建置計畫 II」(2024)專文論述等。

御園生義太〉,《臺灣日日新報》,1928年11月9日,夕刊4版。.jpg)

.png)

-.png)

,1929。1929年《第三回臺灣美術展覽會圖錄》。.jpg)